Sciences. Explanation of the lost magnetism at the meteor impact sites

Madrid, 23 years old (European press)

A scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks has discovered a way to detect and locate the impact sites of meteorites that have long lost their telltale craters.

This discovery could enhance the study of not only the geology of the Earth, but also the study of other bodies in our solar system.

The key, according to work by Associate Professor Günter Klitschka at the UAF Geophysical Institute, is the dramatically low level of magnetization of natural rocks that were subjected to the intense forces of the meteorite as it approached and then hit the surface. .

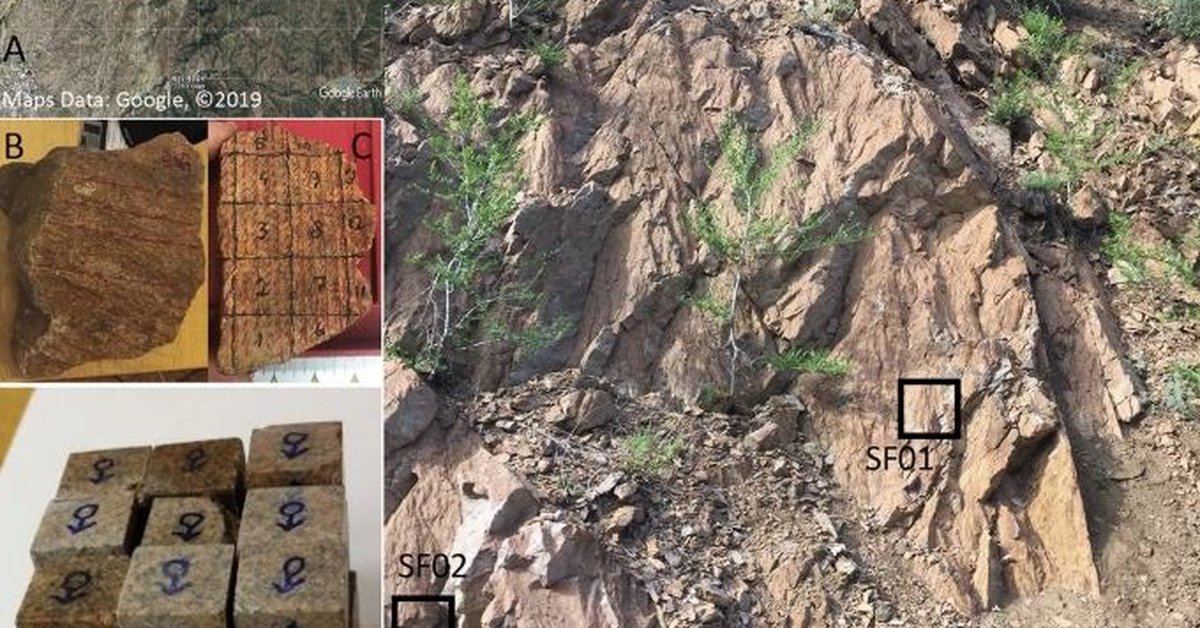

Rocks that have not been altered by artificial or extraterrestrial forces have 2% to 3% natural magnetization residual, which means they are composed of many grains of ferromagnetic minerals, usually magnetite, hematite, or both. Kletetschka found that samples collected in the Santa Fe impact structure in New Mexico contain less than 0.1% magnetism.

Kletetschka determined that the plasma that arises at the moment of impact and the change in the behavior of electrons in rock atoms are the causes of minimal magnetism.

Kletetschka announced his findings in an article published Wednesday in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Santa Fe Impact structure was discovered in 2005 and is estimated to be about 1.2 billion years old. The site consists of easily identifiable broken cones, which are rocks with fan-tail characteristics and fracture radiating lines. It is believed that fractured cones form only when rocks are subjected to a high-pressure, high-speed shock wave, such as a meteor or nuclear explosion.

Kletetschka’s work will now allow researchers to locate the impact site before detecting broken cones and better determine the extent of known impact sites that have lost erosion craters.

“When you have an impact, it’s incredibly fast,” Klitschka said in a statement. “Once there is contact at that speed, there is a change in kinetic energy in heat, steam and plasma. Many people understand that there is heat, and maybe some fusion and evaporation, but people don’t think of plasma.”

Plasma is a gas in which atoms are divided into negative electrons and free-floating positive ions. “We were able to detect in the rocks that plasma was formed during the impact,” he said.

Earth’s magnetic field lines penetrate everything on the planet. The magnetic stability of rocks can be temporarily affected by the shock wave, such as when an object hits a hammer, for example. The magnetic stability of the rocks returns once the shock wave has passed.

In Santa Fe, the impact of the meteor sent a massive shock wave through the rocks, as expected. Kletetschka discovered that the shock wave changed the properties of atoms in rocks by modifying the orbits of some electrons, causing them to lose their magnetism.

Modifying the atoms would allow the rocks to be quickly remagnetized, but Kletetschka also found that the impact of the meteorite had weakened the magnetic field in the area. The rock could not have regained its 2% to 3% magnetism even though it had the ability to do so.

This is due to the presence of plasma in the rocks at the surface of the impact and below. The presence of plasma increased the electrical conductivity of the rock as it turned into vapor and molten rock at the leading edge of the shock wave, temporarily weakening the surrounding magnetic field.

“This plasma will shield the magnetic field, so the rocks will find only a very small field, a remnant,” Klitschka said.