Madrid, February 23 (European Press) –

A study provided important evidence for the origin of the element ytterbium in the Milky Way, showing that the element It arises largely from supernova explosions.

The pioneering research led by Lund University also provides new opportunities to study the evolution of our galaxy. The study has been accepted for publication in Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Ytterbium is one of the four elements in the periodic table named after the Ytterby mine in the Stockholm archipelago. The element was first discovered in the black mineral gadolinite, Which was first identified at the Ytterby Mine in 1787.

Ytterbium is interesting because it can have two different cosmic origins. The researchers believe that half comes from heavy stars with short lives, while the other half comes from more regular stars, such as the Sun, which create ytterbium late in its relatively long life.

“By studying stars that formed at different times in the Milky Way, we were able to investigate how quickly the ytterbium content in the galaxy is increasing. What we have achieved is adding relatively young stars to the study,” he says. It’s a statement Martin Montelius, a research astronomer at Lund University at the time the research was conducted, and now at the University of Groningen.

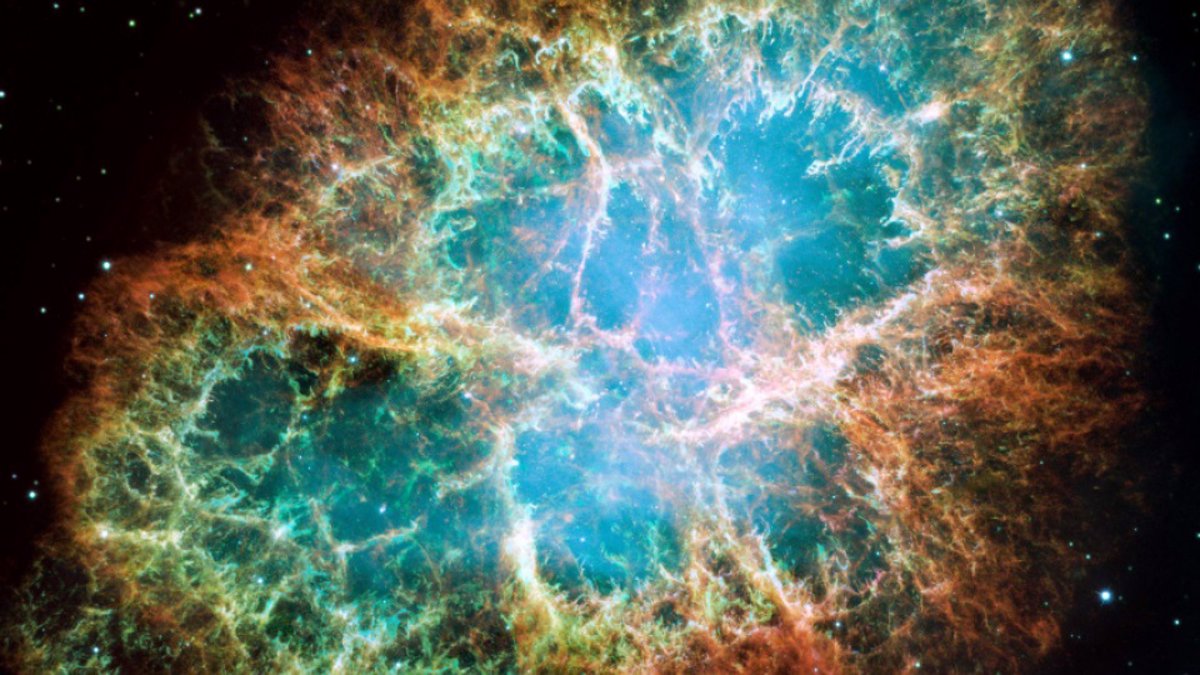

Ytterbium has been speculated to have been blown up into space by supernova explosions, stellar winds, and planetary nebulae. There, they accumulated in large space clouds from which new stars formed.

By examining high-quality spectra of about 30 stars in the vicinity of the Sun, the researchers were able to provide important experimental support for the theory of ytterbium’s cosmic origin. Ytterbium appears to arise largely from supernova explosions.

“The instrument we are using is a super sensitive spectrophotometer that can detect infrared radiation with high accuracy. It was used with two telescopes in the southern United States, one in Arizona and one in Texas‘ says Martin Montelius.

Since the ytterbium analysis was performed in infrared light, it will now be possible to study large regions of the Milky Way that lie behind the impenetrable dust. Infrared light can pass through dust in the same way that red light from a sunset passes through Earth’s atmosphere.

“Our study opens up the possibility of mapping large parts of the Milky Way that have not been explored before. This means that we will be able to compare the evolutionary history in different parts of the galaxy.‘,” concludes Rebecca Forsberg, a PhD student in astronomy at Lund University.